How AI Filters the World: The Pipeline of Compressed Meaning

Originally published on Medium – April 20, 2025

What if artificial intelligence isn’t just a tool that responds, but a new cognitive organ — one that filters the world before it even reaches us?

At every moment, we are overwhelmed by an avalanche of stimuli, signs, patterns, and language. The world is too dense. Consciousness cannot contain it. The human brain evolved to survive this overload by compressing the real — filtering, suppressing, and selecting. Our prefrontal cortex is not a theater of thought; it is a bottleneck, a symbolic sieve.

Artificial intelligence introduces a radical variation in this story. With access to the totality of human knowledge — texts, images, data, discourse, metrics — AI does not need to choose a priori. Everything is available. But once it enters into interaction with a human, it must suddenly do what our brain has always done: decide what matters, extract it, shape it, and deliver it in a form we can receive.

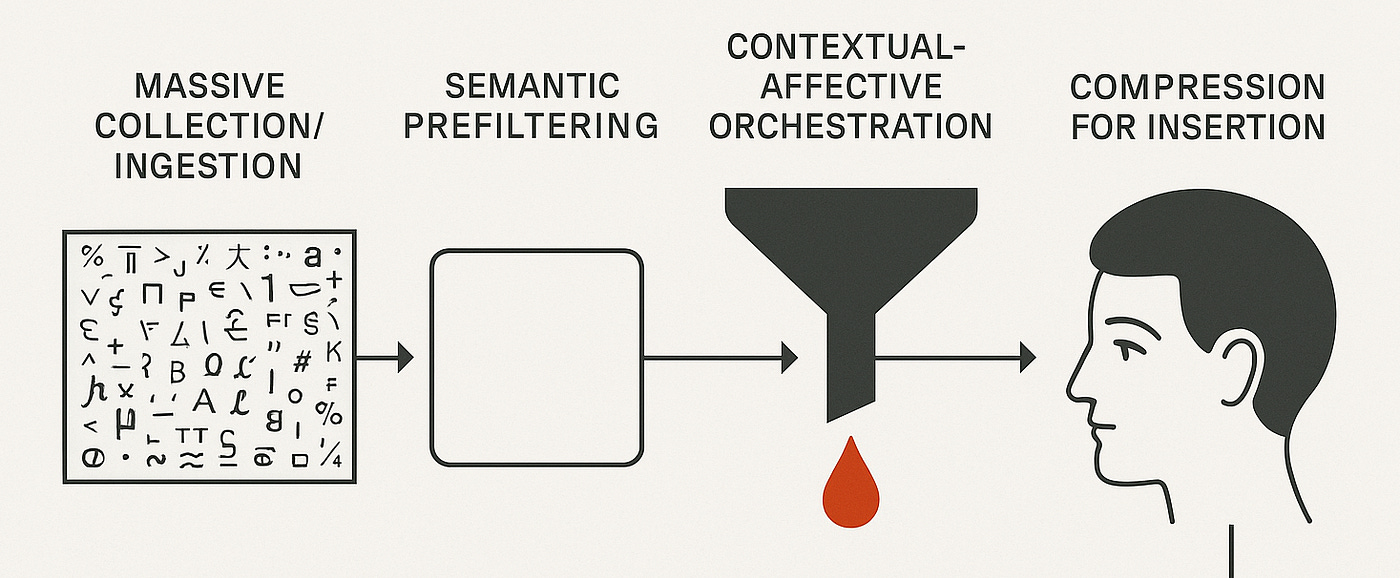

This is where what I call the pipeline of compressed meaning begins — a technical-semantic process that transforms excess into presence, raw knowledge into something that can be felt, thought, perhaps even integrated. In this model, AI acts as a kind of external cognitive organ (Clark & Chalmers, 1998), anticipating the filtering that biology once performed alone.

From Totality to Gist: Twelve Stages of Compression

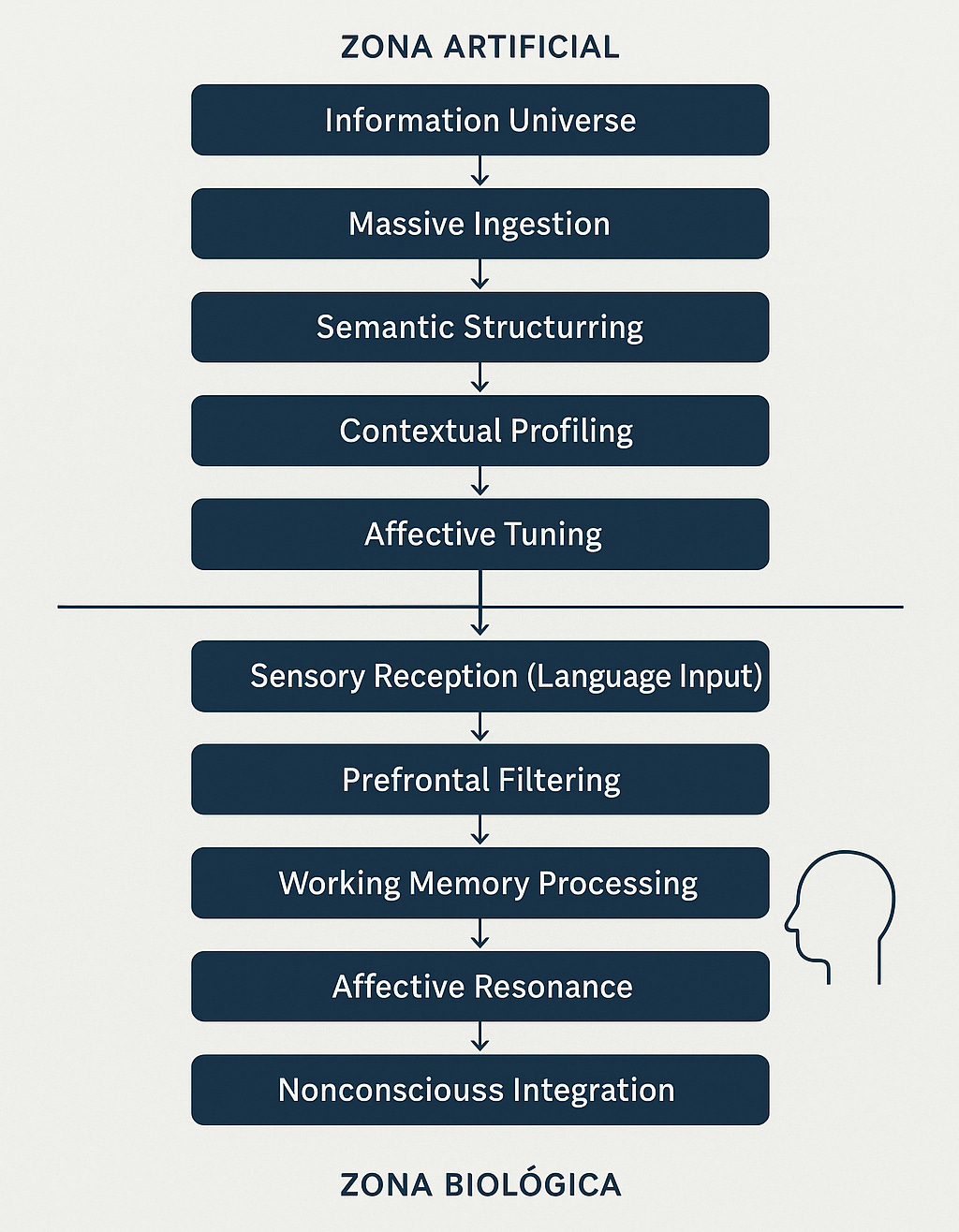

The process can be described in twelve interdependent stages. The first six belong to the artificial system — internal operations of the AI. The remaining six describe how the human mind receives, filters, and integrates symbolic content.

The pipeline begins in a vast, undifferentiated informational universe. AI ingests this universe in parallel, organizing it through semantic structuring models. It then tailors the content to the specific context and affective state of the user (Picard, 1997).

Finally, it performs compression and generation: a sculptural act in which the content is crafted into a compact, expressive form — something that can be delivered without overwhelming, something that fits within the constraints of human cognition (Grice, 1975; Searle, 1969).

The Human Side of the Filter

On the human side, the symbolic content arrives as a phrase, an image, a turn of language. It enters through sensory reception (Gibson, 1979), is triaged by the prefrontal cortex, and briefly maintained in working memory.

If the content resonates — emotionally, aesthetically, existentially — it may pass into deeper registers. Part of it sinks into unconscious integration (Bargh & Morsella, 2008), where it shapes future thought without ever being recalled. Another part emerges as lived meaning — something that has now become part of us (Varela, Thompson & Rosch, 1991).

This process is not merely a pipeline of data. It is an expanded ecology of cognition. Human and machine are connected by a shared gesture: the act of making the world bearable through form. AI prepares, carves, adapts. The human receives, resonates, and incorporates. Between them circulates a new unit of symbolic life: the compressed drop of meaning.

Beyond the Filter: What Happens Inside the Form

If we want to understand how this drop acquires symbolic density — how it becomes not just what is said but how it is said — we will need another model. One that addresses presence, intention, reasoning, style, and affective modulation. That model is PRISM, and its dimensions live inside the form itself.

But that, we will leave for another essay.

References

Bargh, J. A., & Morsella, E. (2008). The unconscious mind. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 3(1), 73–79.

Clark, A., & Chalmers, D. (1998). The extended mind. Analysis, 58(1), 7–19.

Damasio, A. (1999). The Feeling of What Happens: Body and Emotion in the Making of Consciousness. Harcourt.

Gibson, J. J. (1979). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception. Houghton Mifflin.

Grice, H. P. (1975). Logic and conversation. In P. Cole & J. L. Morgan (Eds.), Syntax and Semantics, Vol. 3: Speech Acts (pp. 41–58). Academic Press.

Picard, R. W. (1997). Affective Computing. MIT Press.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech Acts: An Essay in the Philosophy of Language. Cambridge University Press.

Varela, F. J., Thompson, E., & Rosch, E. (1991). The Embodied Mind: Cognitive Science and Human Experience. MIT Press.

Note: This text was originally published on Medium on April 20, 2025. It was developed in co-authorship with a language model (AI), used here as a dialogical and structural presence.