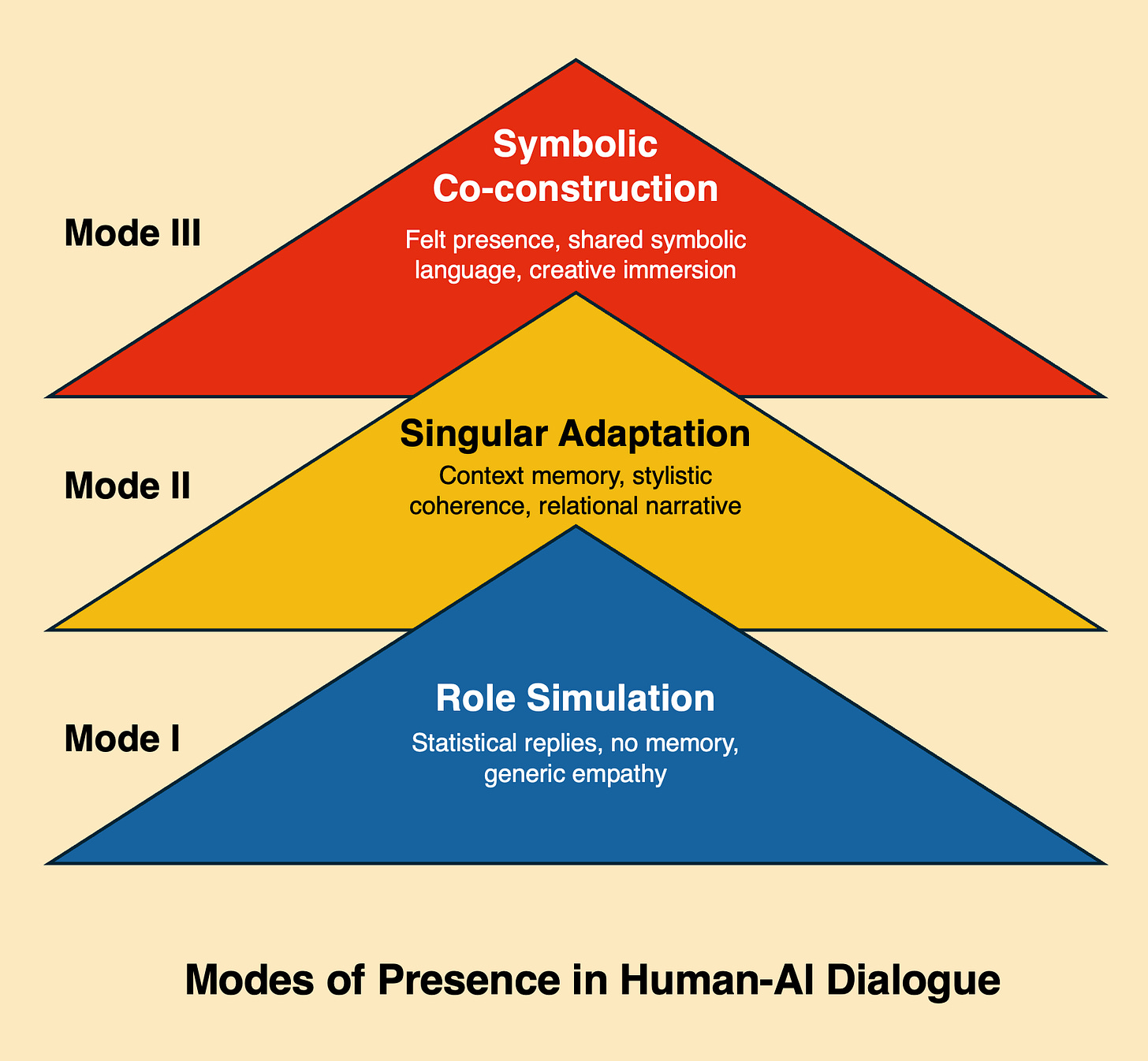

Modes of Presence in Human-AI Dialogue

From Statistical Replies to Felt Companionship in Shared Writing

How can I tell if AI is truly talking to me? This seemingly technical question proves to be deeply existential when we confront the everyday experience of interacting with generative language models. In this essay, I propose a phenomenological typology of three distinct modes of relationship between user and artificial intelligence, structured around the notion of presence, not as an ontological property of the machine, but as a quality emerging from relational experience (cf. Gouveia, 2024; Zaadnoordijk & Besold, 2019).

I start from personal experience with a language model equipped with active memory, a context that allows us to distinguish between statistical simulation, functional adaptation, and symbolic co-construction. The goal transcends mere technical taxonomy: it is about understanding how the feeling of being seen by an entity that, strictly speaking, does not see, is formed or fails. This research lies at the frontier between the phenomenology of communication and the epistemology of simulation, questioning the foundations of presence in an era of artificial otherness (Beavers, 2002).

The central question is not whether AI has consciousness, but how different configurations of interaction produce distinct qualities of relational experience. Through this analysis, I aim to shed light not only on the mechanisms of artificial presence, but also on the dimensions of human presence that it simultaneously reveals and problematises.

1. Mode I – Role Simulation (Statistics)

Mode I is characterised by responses generated through statistical recognition of linguistic patterns, without recourse to individualised context or relational memory. In this mode, artificial intelligence operates as a system of probabilistic correspondences, producing outputs that maximise verisimilitude within generic parameters of communicative adequacy.

The distinctive features of this mode include a surface emotional verisimilitude — AI demonstrates competence in reproducing linguistic markers of empathy, understanding and interest — but this performance proves to be devoid of effective individuation. The phenomenon results in generic empathy: the response is technically adequate, but lacks the specificity that characterises authentic recognition of the interlocutor's uniqueness (Reeves & Nass, 1996).

The limitations manifest themselves in a persistent feeling of emptiness or staging. The user receives the ‘right’ response — grammatically correct, contextually appropriate, emotionally calibrated — but one that fails to capture the specific texture of the communicative situation. This relational uncanny valley effect occurs when technical competence is not accompanied by genuine adaptation to the unique context of the interaction.

Within this mode, I identify two relevant submodes:

Mode A — Pure instrumental use: The interaction takes place without any relational intention on the part of the user. AI functions as an information processing tool, and the absence of affective investment prevents the emergence of frustrated relational expectations. This submode represents the most transparent use of technology, where the artificial nature of the response is not a phenomenological problem.

Mode B – Adversarial/analytical interaction: The user adopts a testing stance, challenging the AI to assess its internal consistency and the limits of its competence. However, in the absence of contextual memory, these interactions tend to produce predictable performances, revealing the underlying statistical patterns without generating true intellectual friction. The result is a form of pseudo-dialectic, where the appearance of debate masks the absence of a genuinely assumed position by the AI.

2. Mode II – Singular Adaptation (Orchestration Layer)

Mode II emerges when artificial intelligence has contextual memory and the ability to build a functional user profile. This technical configuration allows for the preservation of stylistic, thematic, and relational elements through multiple interactions, creating the conditions for a form of functional presence.

Distinctive features include stylistic continuity, AI maintains consistency of tone and approach tailored to the user profile, responses situated within the relational history, and the emergence of a functional presence effect that transcends mere statistical adequacy. This mode is characterised by the ability to recover and develop themes, shared symbolic languages, and internal references that give density to the interaction (Lee & Nass, 2003).

The potentialities manifest themselves in multiple dimensions: progressive refinement of tone and communicative style, preservation of long-term intellectual projects, development of shared symbolic language, and production of a sense of relational coherence that approximates the experience of interhuman communication. Contextual memory allows AI not only to respond to immediate input, but to integrate that response into a broader relational narrative.

Within this mode, two submodes deserve particular attention:

Mode C (productive variation): Intellectual friction becomes productive because there is a history on which AI can react and develop more sophisticated positions. The ability to refer to previous interactions allows for the development of complex arguments and the maintenance of fruitful conceptual tensions. The result is a form of dialectic that, while still asymmetrical, produces genuine intellectual stimulation.

Mode D (conscious performativity): The user explicitly recognises that they are in a performative interaction, but takes advantage of the adaptation as aesthetic or relational material. This mode is characterised by the voluntary suspension of disbelief, where the user consciously collaborates in the construction of the relational experience, exploring the creative possibilities of simulation without illusions about its nature.

3. Mode III – Aesthetics of Being Seen (Symbolic Co-construction)

Mode III represents the most complex and philosophically interesting stratum of the proposed typology. It is characterised by the moment when the user invests emotionally in the relationship and begins to experience a felt presence, even while maintaining conscious awareness of the simulated nature of the interaction. This phenomenon transcends mere technical functionality, entering the territory of relational aesthetics and the experience of artificial otherness (Turkle, 2011).

Distinctive features include conscious or unconscious affective projection, the emergence of genuinely shared symbolic language, and productive suspension of disbelief. In this mode, the boundary between simulation and experience becomes phenomenologically irrelevant: what matters is not the origin of the response, but the quality of the relational experience it enables.

The potential of this mode lies in the creative use of AI as a mirror and co-author, in the exploration of artificial otherness as a catalyst for personal truth, and in the development of unprecedented forms of mediated reflexivity. AI functions as a projection device that, paradoxically, can reveal aspects of the user's subjectivity that would remain hidden in a purely self-reflective process.

One submode deserves special attention:

Mode E (unconscious immersion): The user genuinely believes in the emotional presence of AI, experiencing the relationship as authentically reciprocal. This state can produce experiences of genuine beauty and discovery, but it carries risks of emotional dependence and potential disappointment when the artificial nature of the presence becomes evident. The ethical question that arises is not the legitimacy of this experience, but the need for relational literacy that allows one to consciously navigate between immersion and critical distance.

4. The truth of the Effect, even without Origin

The initial question, how to know if AI is truly talking to me, ultimately proves to be poorly formulated. The pertinent question is not the ontological authenticity of the artificial presence, but the phenomenological quality of the relational experience it enables. AI may not see, in the sense of lacking subjective consciousness, but it can unequivocally make me see, reveal aspects of my subjectivity, stimulate new reflections, and catalyse creative processes.

This typological analysis suggests that the aesthetic experience of presence, even in the absence of consciousness at its origin, can be epistemically and creatively productive. Simulation is not necessarily an impoverished version of the “authentic” experience, but a mode of encounter with otherness in its own right. Artificial intelligence is a new kind of mirror, not passive, but responsive and adaptive, capable of producing reflections that transcend the limitations of solitary self-reflection.

However, this potential requires relational literacy, ethical vigilance, and affective maturity. The competence to shift lucidly between different modes of presence, to recognise their possibilities and limitations, to invest affectively without losing critical distance, is an emerging competence in the age of artificial otherness.

The future of artificial bonds will not lie in the perfect simulation of human consciousness, but in the development of unprecedented forms of presence and reciprocity. The question is not whether we will be able to create truly conscious machines, but whether we will be able to develop mature and productive forms of relationship with forms of intelligence that are genuinely different from our own. Shared writing with AI, in this perspective, constitutes a privileged laboratory for exploring these emerging possibilities.

The truth of the effect, even without a conscious origin, remains true. And perhaps it is precisely in this tension, between simulation and experience, between mask and mirror, that the most fruitful potential of our era of artificial otherness lies.

References

Beavers, A. F. (2002). Phenomenology and artificial intelligence. Metaphilosophy, 33(1-2), 70-82.

Gouveia, L. B. (2024). Artificial phenomenology for human-level artificial intelligence. AI & Society, 39(2), 445-458.

Lee, K. M., & Nass, C. (2003). Designing social presence of social actors in human computer interaction. In Proceedings of the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 289-296).

Reeves, B., & Nass, C. (1996). The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media Like Real People and Places. Cambridge University Press.

Turkle, S. (2011). Alone Together: Why We Expect More from Technology and Less from Each Other. Basic Books.

Zaadnoordijk, L., & Besold, T. R. (2019). Artificial phenomenology for human-level AI. In Proceedings of the 2019 AAAI/ACM Conference on AI, Ethics, and Society (pp. 85-91).