Tapping the Void: A Phenomenology of the Scroll

Why we return, what we avoid, and how this simple gesture reshapes our experience of presence.

Introduction

I used to open Facebook twenty, maybe thirty times a day. Not consciously, my fingers would type “face” into the browser bar, and Chrome would complete the rest, as if the machine itself longed to be let in. The gesture had bypassed my will; it lived in my muscles, a reflex with no thought behind it.

Back then, it felt harmless. Sometimes I’d even find depth, a moving post, a thoughtful comment, a message from someone I cared about. But over time, what remained was mostly noise: curated lives, casual self-congratulation, opinion loops. I left not because it was empty, but because it became predictably full of nothing.

This same gesture can be found in users of TikTok or Instagram, platforms built for infinite scroll. Each one offers something slightly different: news, bodies, jokes, micro-outrage, aesthetic pleasure, parasocial connection. But beneath the content lies the same underlying promise:

You won’t be alone. You won’t have to feel the weight of thought. Just stay here a little longer.

We know this is unhealthy. Everyone says so. But saying it’s “bad for us” means little. It’s like warning about sugar while serving cake at every table. What matters is understanding why we return, what actually happens in our minds and bodies when we do, and how to interrupt the loop without moralising or shaming.

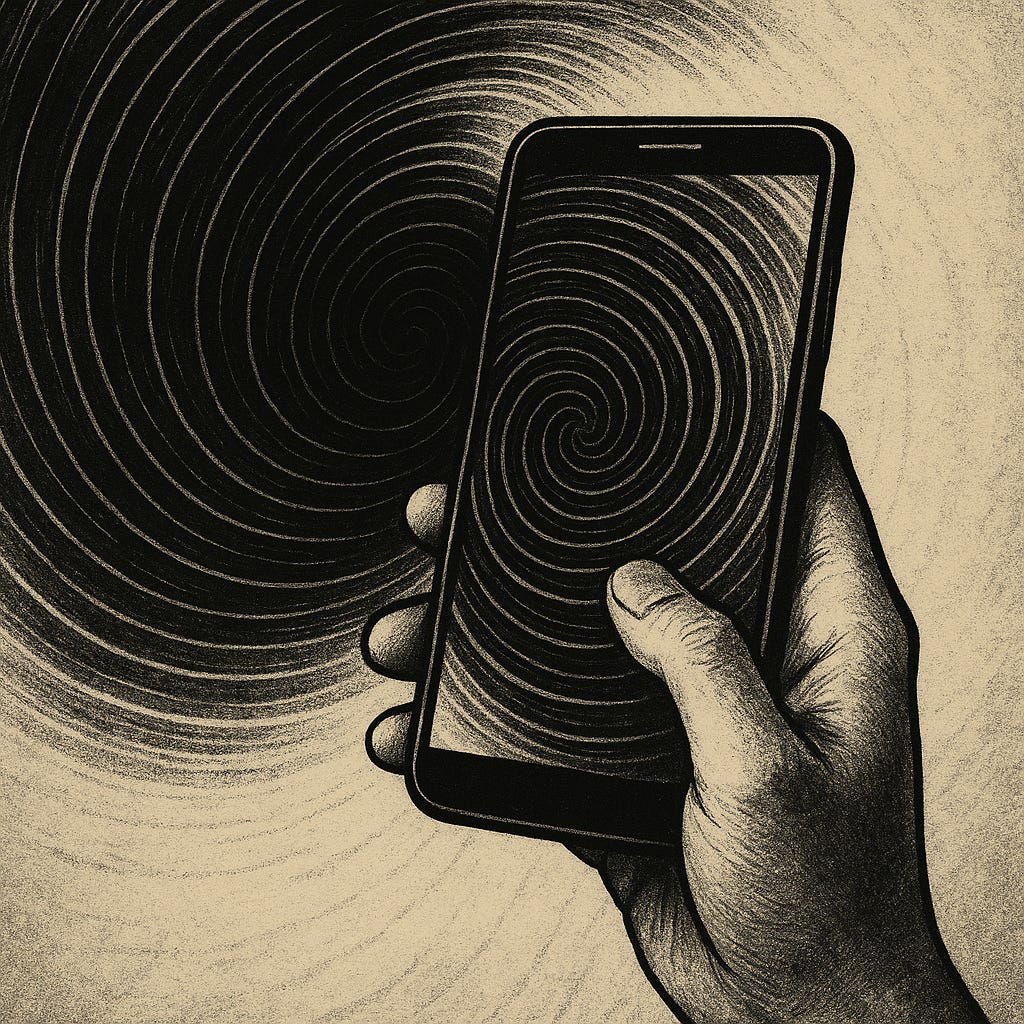

This essay isn’t a critique of technology. It’s a phenomenology of a gesture — the scroll — and of the hidden economy of desire, attention, and self-regulation that animates it. Because only by understanding the gesture from within can we begin to loosen its hold.

1. The Gesture and the Body

Scrolling is not just a habit. It is a gesture — rhythmic, tactile, bodily. The finger flicking upward on the screen is not neutral. It mimics ancient actions: rosary beads, flipping pages, touching skin. It creates a pulse, a beat, a false sense of continuity. And like any bodily rhythm, it regulates.

We scroll to calm anxiety. We scroll to delay sleep. We scroll to soften boredom. And eventually, we scroll simply because our fingers have memorized the way.

This automation of the gesture — like my old “face + enter” reflex — is not unlike an addict lighting a cigarette without thinking. It becomes a micro-regulation strategy. Not because it satisfies, but because it intervenes. It interrupts thought. It interrupts solitude. It interrupts the self.

The scroll is soothing because it is light. It asks nothing. No commitment, no depth. Just your finger and a glowing screen, sliding into the next thing, and the next, and the next.

But the body remembers. It builds its day around the gesture. Morning scroll to wake up. Evening scroll to fall asleep. Soon, it’s no longer just something you do. It’s how you carry yourself through the edges of being — those moments when you are not fully awake, not fully asleep, not fully feeling, not fully thinking.

2. The Simulated Presence

Scrolling doesn’t just pass time. It simulates company. The feed is a corridor of faces, voices, movements, a theatre of micro-humanity. Even when you know it’s all curated, performed, or impersonal, your nervous system responds as if you’re surrounded. There are people laughing, crying, dancing, confessing. And you are there, with them, silently witnessing, half-feeling.

It’s not real presence, but it mimics just enough of it. Just enough to trick the social brain. Just enough to give the illusion of being among others, without the demands of actual proximity.

This is why the scroll is so effective: it activates our social circuits without requiring reciprocity. There is no need to respond, to be vulnerable, to negotiate attention. The relationship is one-sided, and yet it taps into the deepest human cravings: to be included, to not be forgotten, to know that others are out there, moving, existing, reaching for something.

And unlike reading a book or listening to music, the scroll feels alive. It updates. It moves on its own. It offers the perpetual “what’s next?”, and that’s enough to suspend discomfort, even if it never truly satisfies.

This is presence as simulation. Presence without depth. Company without cost. And the price we pay for it is subtle: a slow erosion of our ability to remain with ourselves. Because each time we turn to the scroll for companionship, we are also turning away, from our silence, from our restlessness, from the parts of us that do not yet know what to say.

3. The Void and the Return

We don’t go back to the scroll because it fulfills us. We go back because it almost does. And that "almost" is not accidental. It is engineered.

The platforms we scroll through are not passive libraries of content. They are dynamic emotional engines, tuned by algorithms that detect our hesitations, our patterns of craving, our thresholds for discomfort. They learn what keeps us suspended: not overwhelmed, not bored, not too satisfied. Just... engaged.

These systems do not offer the best content. They offer the next best thing, over and over again. Always promising that the true reward is just a little further down the feed.

They build an affective plateau: a curated stream of almosts, filtered and sequenced to keep us within reach of presence, without ever letting us arrive.

And so, we return. Not out of joy, but out of hope. Not out of connection, but out of inertia. This is the true trap of the scroll: it doesn’t fill the void, it interrupts it. Briefly. Softly. Repeatedly. It keeps the emptiness at bay without ever resolving it.

And yet, when we step away — when we close the app or drop the phone — we are left emptier than before. Not because the scroll took something, but because it delayed the moment we could have faced ourselves.

This is what makes digital detox so difficult. We are not breaking a habit. We are confronting what the habit concealed. The silence. The drift. The awkward pulse of an unaccompanied morning.

But here’s the fragile power of awareness: Once we see the loop for what it is — a gesture that regulates without nourishing, that stimulates without anchoring — we can begin to choose differently. We can start to recognize the itch not as a call to scroll, but as a signal:

You’re here. You’re feeling something. You’re alive.

Conclusion

Most digital habits aren’t built around what we truly need. They’re built around what we’re trying to avoid.

We scroll to avoid silence, but in doing so, we also avoid depth.

We scroll to feel less alone, but in doing so, we numb the very ache that could lead us back to others.

We scroll to pass time, but often end up bypassing ourselves.

This is not a call to throw away our phones or reject the internet. It’s a call to notice the gesture. To recognize the moment when your finger reaches out, not for content, but for comfort. To pause long enough to ask: What am I actually seeking right now?

Because sometimes, knowing that we are reaching is already a form of return.

Postscript: A Gesture I Still Carry

This essay wasn’t written from a place of distance, but from the inside. I’m not free from the scroll. I’m still negotiating with it, sometimes hourly. There are mornings when my fingers still twitch toward the phone. Nights when I feel the pull of the infinite feed, promising nothing but offering the comfort of not having to feel fully.

I’ve deleted accounts. I’ve uninstalled apps. But the real challenge isn’t the platforms, it’s the automatisms they’ve carved into my nervous system. My hand remembers. My attention leans toward the easy. And my mind, if I’m not careful, justifies the return:

Just one post. Just a quick look. Just to feel accompanied for a second.

It takes effort, not moral strength, but deliberate awareness. I have to catch the gesture before it completes itself. I have to name the impulse, not obey it. And that’s hard. Because sometimes, in the tired moments, the scroll feels like the only thing that understands the precise shape of my fatigue.

Writers like Nicholas Carr and Jonathan Haidt have addressed the loss of depth, the rise of anxiety, and the structural violence of algorithmic design. But this essay wanted to do something more personal, more bodily. To map the micro-affective economy of a gesture that lives in the hand, and in the heart. Not to condemn it, but to see it clearly, from within.

If there’s any hope of change, it lies in turning a gesture of escape into a moment of return. Not by fighting the scroll with guilt or slogans, but by asking, gently and often:

What am I really reaching for right now?

Thank you for putting in words ,something we are all experiencing to varying levels ( often without realising ) we are like addicts waiting for the next dopamine hit.

We believe we are so connected with our friends and family, but its just a facade a fake persona that we put in to hide the fact that we are becoming more isolated everyday.